Deportation regimes – informing the politicised debate

Anthropologist Barak Kalir unravels the highly politicised context in which deportation takes place. He offers policymakers and practitioners in the field a critical perspective on current deportation regimes, their (in)effectiveness, and an alternative approach to illegalised migrants.

A political agenda and firm opposition

Illegalised immigration and deportation are increasingly acute social issues with a clear political and socio-economic resonance, which dominate the political agenda of many, if not all, developed and developing countries. Public and political debates are highly influenced by negative framing of illegalised migrants. The overall concern seems to be the costs of illegalised immigrants to society and their potential threat to the cultural and social unity of the nation.

Within the field of deportation, state institutions and civil society organisations are allegedly offering firm opposition. Policymakers, bureaucrats and other state agents are placed on one side, whose explicit goal it is to enforce the law and ensure the repatriation of illegalised migrants. Volunteers and salaried workers in civil society organisations are placed on the other side, contesting state deportation policies and assisting illegalised migrants based on human and universal rights.

Talking to the people on the ground

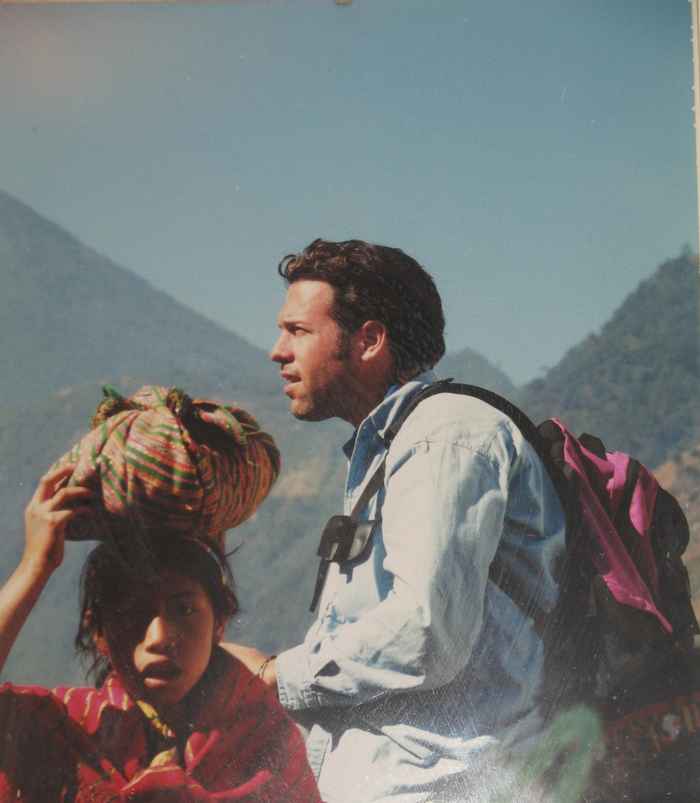

In 2014, Barak Kalir and his research team received funding from the European Research Council to study and compare the actual workings of deportation regimes in four different states: Israel, Greece, Spain and Ecuador. The team decided to focus on the practices, motivations and world views of street-level state agents and civil society actors who are involved in the daily process of deportation. They spoke with police agents, personnel in detention centres and officials in asylum shelters, who define, locate, detain and deport illegalised migrants and so-called ‘failed’ asylum seekers. In addition, they interviewed actors in local and international NGOs, grass-roots movements and religious organisations, who aim to protect the rights of illegalised migrants and prevent their deportation.

The support for and effect of deportation is much more biased

The research brings to light the workings of these actors in relation to the tension that is produced by the letter of the law and the private convictions of those who are implementing it. It shows how these actors perform their jobs while maintaining different private views on deportation. The firm opposition between state institutions and civil society organisations turns out to be much more nuanced in practice, while the support for and the effect of deportation are much more biased.

Both sides show significant convergence in their treatment of illegalised migrants, the usage of terminology, handling of face-to-face interactions, and world views on issues such as national belonging, justice and the need to protect the borders of the nation-and-state.

Sharing research results

Barak and his team contribute to and nuance the highly politicised public and political debates. Through their insight into the actual operations of deportation regimes and the comparison between various countries, they bring to light not only the effectiveness or ineffectiveness of deportation regimes but also the potential conflict between these regimes and fundamental rights on the level of both the state and the individual.

Kalir is convinced that social science research is crucial in times of change, when policy makers need scientific knowledge to adjust to that change. Influencing policymakers when there is no felt need for change, he believes is more difficult. Kalir and his team have chosen to focus on sharing knowledge and results with activists and practitioners in the field who are more willing and able to use that knowledge to reflect on their daily work and to mobilise resources and actions in order to bring a change in existing policies.

The team reaches out to NGOs, activists, policymakers and the broad public by publishing in national news media, blogging on social media, giving public lectures, organising workshops and trainings, and working together with renowned documentary makers.

The example of Spain: reaching activists, schools and judges

In Spain, for example, the research team reached activists through interviews and dialogues, and helped them to reflect on their specific role in the operations of deportation regimes, mostly through their involvement in facilitating so-called ‘voluntary return programmes’. While the activists’ mission was to contest deportation, research showed that they were forced into a role of support by their humanistic standpoint and the resulting aid which they offered to illegalised migrants, leading to their return.

The PI took part in a documentary about a specific and well-known deportation case which was broadcast on national television. This documentary shifted public opinion on irregular migration and opened up policy discussions about the effectiveness of current regimes. The documentary was also shown to the European Committee in Brussels and is now broadcast at schools to provide pupils with a more informed story of deportation regimes.

Finally, also in Spain, the research results are being incorporated in the training of judges who have to decide on the detention of illegalised migrants facing deportation.