Why Academic Writing Loses Readers — And Why It Matters

1 December 2025

If you open an academic article today, you quickly sense that the language is not designed to be easy to understand. Pages full of abstract terminology, endless sentences, and overly theoretical language often obscure rather than illuminate. The outcome is predictable: even important research risks losing its audience. We live in an era of open access and “science for all,” yet academic writing has somehow managed to remain inaccessible to many readers. This is rarely intentional, of course, but neither is there a structured effort to make scholarly texts more understandable. The result is a style of writing that excludes more than it includes. Assistant Professor Robbin Jan van Duijne described it during the session as a language in itself — what he called academese.

Curse of knowledge

One explanation for this tendency is what Steven Pinker calls the “curse of knowledge.” The more deeply immersed we become in our fields, the harder it is to remember what is intuitive and what is not. Words like ontological, interoperability, deterritorialization, or hegemony start to feel natural, and soon they appear everywhere in our writing. But readers outside our niche—students, colleagues from other fields, policymakers, or community partners—can easily feel shut out.

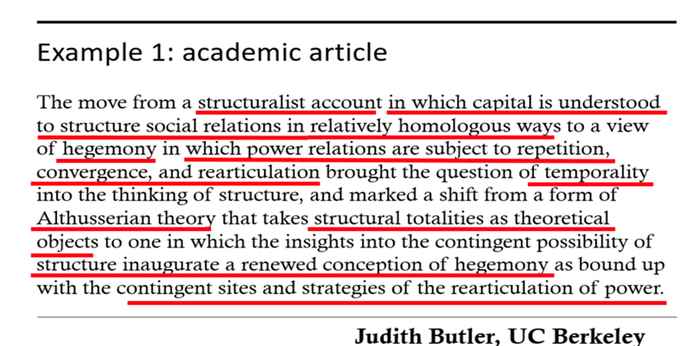

Several examples presented in the seminar demonstrated how dense academic prose often hides surprisingly simple ideas. A well-known sentence by Judith Butler, packed with theoretical references and 21 prepositions, becomes clear and accessible once translated into everyday language. The same holds for overly technical theses or grant proposals: once simplified, their arguments become sharper and more persuasive. This matters not just for readability; in the case of funding applications, it can determine whether research gets supported at all.

Influence of LLM's

Another growing challenge is the influence of large language models, which replicate the tone and style of the academic texts they were trained on. As a result, academese spreads even faster, showing up in student essays and reports that sound sophisticated at first glance but lose precision and meaning when examined closely.

However, it is important to note that the problem is not complexity itself. Complex ideas often require layered, nuanced explanation. But clarity is what allows that complexity to be understood. When dense wording and unnecessary jargon are stripped away, what remains is not a loss of intellectual depth but a gain in comprehension: readers can grasp the core insight instead of struggling to navigate the terminology.

Shared understanding

Ultimately, the seminar offered a straightforward message: we should write to communicate, not to impress. Clear writing reaches more people, makes our arguments stronger, and opens academic work to a wider community. It supports students, colleagues, partner organisations, and the public, ensuring that knowledge is not trapped behind complicated language. If the purpose of academia is to build shared understanding, then clarity is not optional but a responsibility. Writing with openness, precision, and generosity is one of the most effective ways to ensure that our research truly has an impact.