Studying healthcare ethics through an anthropological lens

15 December 2022

Post held the Socrates chair in Social Theory, Humanism and Materiality at the department of Anthropology for ten years. This Special Chair has now been converted into a joint chair of the Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences and the Faculty of Medicine. She will spend half of her working week at the department of Anthropology and half at Ethics, Law & the Humanities at Amsterdam UMC. She is greatly looking forward to this form of multidisciplinary cooperation. ‘This is the greatest challenge, but we have a lot to offer to each other.’

Observing daily healthcare practice

The chair is called ‘Anthropology of everyday ethics in healthcare’ – quite the mouthful. What exactly does this mean? ‘It’s about the method we use in anthropology to study how people and their technologies try to do good,’ Pols explains. ‘This involves qualitative research, such as interviews and focus groups, but in particular it involves making observations in various healthcare practice settings. Rather than just reflecting on what it would be a good thing to do, we look at how people give shape to ethics in their daily healthcare activities.’

‘Doing the right thing’ in healthcare, says Pols, is providing good healthcare – but just what this involves is not always clear-cut. ‘For example, good healthcare in healing a bone fracture has a clear end goal: to make the person better. But this end goal is not in play in the case of many chronic illnesses or permanent handicaps. People cannot be cured; they have to learn to live with their illness as best they can. What this means can be different every day and will change over time. So how to determine what is good healthcare in those cases?’

Ideals and needs can clash

According to Pols, this requires different methods and criteria. Healthcare processes need to be examined, as do the effects of working on the basis of different ideals. ‘For example, self-reliance and self-management are important ideals in Dutch healthcare. But studies have shown that many chronic patients, in fact, feel a need for advice, consultation and contact. In such cases, ideals and technologies geared towards self-reliance are out of step with what people find important. This also changes the way people use technology.’

Knowledge mismatch

As Pols sees it, there is currently a degree of mismatch in knowledge about healthcare. ‘Healthcare workers build up a lot of knowledge because they treat specific cases. The knowledge handed to them by medical science, however, often involves generalisations about groups or populations in large data sets. This has its use, but such knowledge has to be converted to make it useful for specific clinical cases. Learning about specific cases is precisely what anthropology is good at and where it can make a difference.’

Pols will not only use anthropological methods to gain a better understanding of what constitutes ‘good healthcare’; she will also widen her scope. ‘The academy can be seen to have a great diversity of methods. Sometimes, its image of itself is that there is only one truth-based scientific method. This risks losing sight of the fact that different methods result in different types of knowledge.’

Education

Part of this chair involves designing education, such as practical training in ethics for medical students and fieldwork methodologies in healthcare for anthropology students. ‘It’s great to see that medicine is increasingly taking an interest in qualitative research and in the quest to know what is happening in healthcare practice. My hope is to promote that same awareness and interest in students.’

Social mission

Pols conceives of her chair as having an important social mission. ‘We currently have a whole range of solutions for healthcare, but we often forget to look just where the problems crop up. We continually call out healthcare, but in doing so we sometimes overlook the essence of what healthcare is about.’ Pols believes the guiding principle should not be where we can save money, but the question of just what kind of healthcare we want. We can then look at how much we’re prepared to spend to achieve this and how best to organise it. In order to strengthen healthcare practice in these respects, Pols eventually also wants to translate the acquired scientific knowledge into practice.

The chair was created on 1 September 2022 and will exist for an indefinite period.

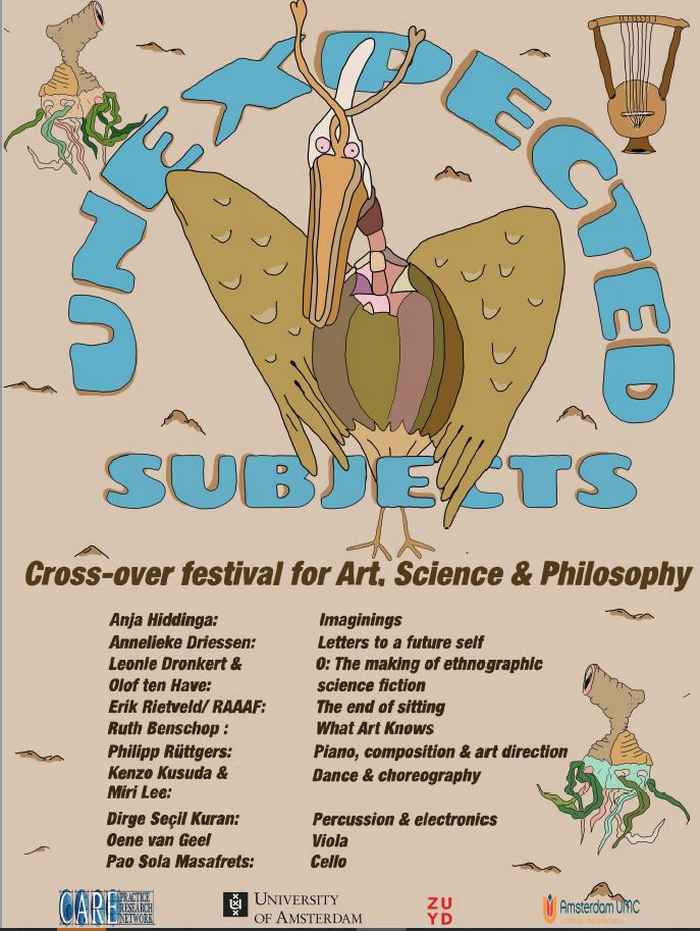

Crossover festival of Philosophy, Art and Science

On Thursday, 29 June 2023 Pols will organise the crossover festival ‘Unexpected subjects’ as part of her inaugural lecture. This festival will acquaint the public with various ways in which art, philosophy and the social sciences can reinforce each other to meet current issues and societal problems. The festival is aimed specifically at ‘care’ and the inclusive society. Activities will include a showing of a poignant, poetic film made by visual anthropologist Anja Hiddinga together with six deaf performance artists, an exhibition of paintings and a letter project by Annelieke Driessen about daily life with dementia, and a presentation by PhD researcher Leonie Dronkert about a science-fiction film she created together with her ‘research subject’ Olof ten Have. Four musicians and two dancers examined the various themes through a confrontation between musical styles and the ‘disciplines’ of dance and music.