Welfare chauvinism: a persistent virus for the welfare state

1 October 2024

What is welfare chauvinism?

Welfare chauvinism is the idea that social benefits and services, such as unemployment benefits, social housing, education and health care, should only be available to ‘native‘ people and not to migrants, refugees or ethnic minorities. The basic principle of welfare chauvinism is welfare for ‘us‘, but not for ‘them‘, explains Gianna Eick. ‘Welfare chauvinism is based on the misconception that newcomers usually abuse the welfare state. The fear is that the biggest tax profiteers are the newcomers, not the native people. This perspective can be found not only in public opinion, but also in election campaigns or laws that exclude newcomers.’

Welfare chauvinism is a winning formula for the radical right.

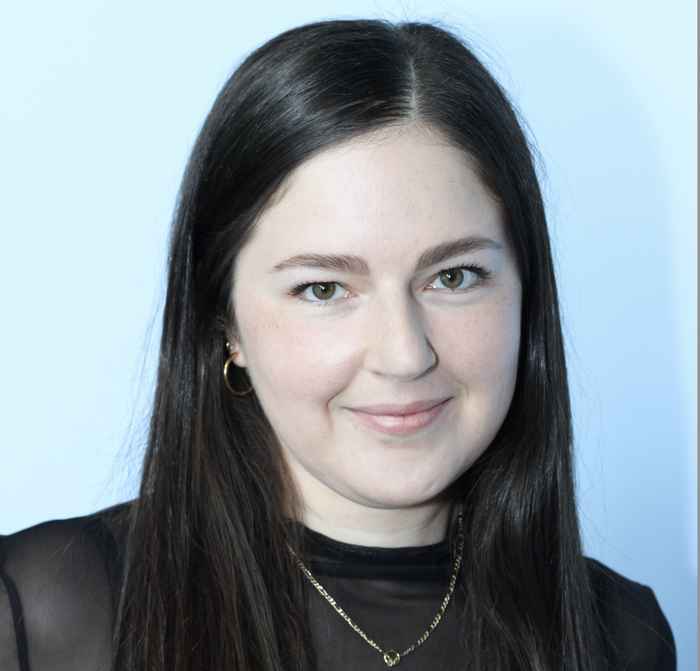

Gianna Eick, an assistant professor of Political Science at the University of Amsterdam, has been interested in migration and social equality from an early age. As a teenager she experienced the benefits of a welfare state at close quarters, using assisted living from youth care and being supported by social assistance. Before moving to the Netherlands, Eick has lived and worked in several countries, including Germany, the UK and Mexico. ‘These experiences have shown me how much governments shape people’s life experiences and opportunities and, at best, can create solidarity between different groups in society.’ By examining both individual and institutional factors, Eick provides valuable insights into the causes and consequences of welfare chauvinism.

A hostile environment

Where does this negative attitude towards newcomers come from? ‘There are various individual and contextual factors, such as uncertainty in the labour market or fear of strangers (xenophobia), that can lead to more welfare chauvinism.’ In addition, politicians also make eager use of this sentiment and use it to mobilise voters. Take, for example, Geert Wilders, who has wanted to curb immigration into the Netherlands for decades.

‘Welfare chauvinism is a winning formula for the radical right, that wrongly accuses newcomers of being the cause of social and economic problems. Established political parties have been adopting this position as well, in part to win back voters from the radical right. Many voters see migration as a major problem exactly because many parties pay so much attention to it. Eventually, voters tend to opt for the radical right party because it has already spoken out on this issue before. This has negative consequences for the welfare state, because right-wing parties tend to gut social policies when they win elections.’

Gianna Eick understands that welfare chauvinism is an appealing sentiment. ‘If the politicians you trust tell you that migration is bad for the country, you're more likely to believe them. It’s only human to want to protect your living standard. However, many people don’t realise that voting for a right-wing party is likely to widen the gap between rich and poor and weaken democracies.’

Education is not the problem

Lower-educated people are often perceived as the largest group with anti-immigration views, but Eick is keen to put this rumour to bed. ‘In the Netherlands, the level of education has little influence on the degree of chauvinism, while in Finland or Russia, it’s the highly educated who are linked to a stronger sense of welfare chauvinism. It’s vital that we don’t stare ourselves blind on individual factors, as this only leads to more polarisation. That’s why it’s all the more important to hold people and institutions in positions of power accountable.’

The child benefit scandal

Welfare chauvinism can manifest itself in various forms and Eick argues that the child benefit scandal is a leading example of a consequence of welfare chauvinism in the Netherlands. Here, tens of thousands of parents and caregivers were falsely accused of fraud by the Dutch tax authorities. Many families went into debt and ended up in poverty. ‘It was a negative spiral: There was a negative public opinion about Eastern European migrants who benefited from Dutch allowances. The media highlighted the problems surrounding this group. And the Dutch tax authorities paid extra attention to “foreign-sounding names” and people with dual nationality. As a result, ethnic minorities were disproportionately discriminated.’ On top of that, the child benefit scandal is not an isolated case in the Netherlands: earlier this year, the Minister of Education apologised for discrimination related to the basic student grant. Students who lived in neighborhoods with a high number of residents with a migration background were more likely to be checked, without any justified reason for it.

Making contact

In order to combat welfare chauvinism, important changes must be made in both social and political areas. Investment in public services, such as education and the labour market, should reduce inequality. Contact between natives and newcomers is also important. Eick: ‘When you get to know newcomers, you discover their life stories. You probably have more in common with them than you think. These meetings can take place at universities, at sports clubs or in community centres. The government can stimulate these kinds of initiatives through social investment policies.’

An inclusive and just society

Gianna Eick’s book Welfare Chauvinism in Europe provides a comprehensive analysis of the complexity behind this problem. The award of the Veni grant will allow Eick to explore further how social investment policies can be used to tackle welfare chauvinism. And she is hardly lacking in motivation. ‘I’d never have been here without government help when I was younger. It’s sad that there’s so much distrust of newcomers who are in need of support. Also because research shows that many people in this situation are ashamed to admit that they need help. With my Veni project, I hope not only to contribute new scholarly findings, but also to contribute to a more inclusive and just society.’